Redemptive Suffering: Pain, Prison, and Assisted Suicide.

The second reason, which can always be counted on to exploit the first, is political: the belief that pain is fundamental to justice, which makes perfect sense if justice is conceived as nothing more than a system of punishments and rewards. The essence of punishment is pain. Whoever owns pain owns power.

But this isn’t a case about who’s responsible for ending a life. All patients who seek a death with dignity have already been meted out a sentence of death, either by cancer, multiple sclerosis, or some other painful, debilitating disease. Who ends a life that is already ended is not what advocates on both sides are contesting. The heart of Baxter v Montana – and the assisted suicide movement in the US – is really: Who has jurisdiction over suffering?

There are at least four bodies within society that have historically laid claim to the realm of suffering, either directly or indirectly: the state; the medical profession; God (or the church); and the individual patient.

From ReligionDispatches today comes an interview with Caleb Smith, the author of the new book, The Prison and the American Imagination, that, when viewed through the lens of the aid in dying movement, sheds much new and needed light on religion, suffering and redemption. In it Smith states:

The reformers who built the model institutions of the early nineteenth century called them penitentiaries, to compel penitence. They drew from Christian traditions—Quaker tenets of nonviolence, Catholic and Calvinist varieties of asceticism and moral rigor—and they often represented the cell as a place of spiritual rebirth. As a precondition for that resurrection, they led convicts through mortifying processes including “civil death,” a loss of legal personhood with origins in European monasticism. The Philadelphia reformer Benjamin Rush quoted scripture in describing the rehabilitated convict as a man who “was lost and is found—was dead and is alive.” My book is animated by my fascination with this resurrection plot and all of its contradictions.

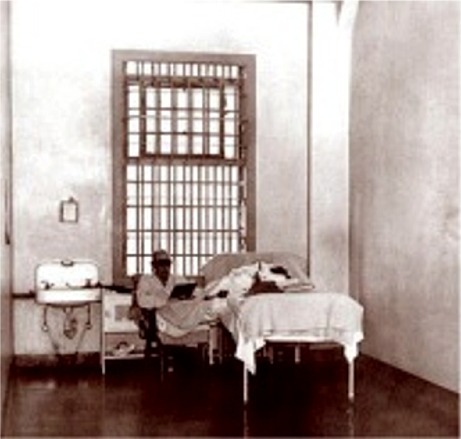

Can hospitalization be considered a form of incarceratin? Smith reminds us of the interwoven nature in Western society of state power and church theology.

Ideas of salvation and redemption not only govern how we treat those who have offended society in criminal ways, but of those who, as Susan Sontag might put it, offend society by contracting terminal illnesses.

Labels: aid in dying, assisted suicide, prison, redemption, suffering

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home